Several years ago, Herman Miller approached Rolf and Mette Hay, co-founders of Danish design house HAY, with a flexible provocation: What could the two design companies do together that they could not independently? The answer: a fresh take on furniture originally designed by Ray and Charles Eames.

To Mette Hay, the challenge was both inspiring and daunting: “I went to the archives to look for something that could put me on the right track. I thought at first it was going to be too difficult, but it would be more terrible to miss the opportunity… It felt like a big ask to touch something that is so untouchable,” she recalls.

“Then l remembered looking at this amazing Alexander Girard textile called Jacob’s Coat with Tony Manzari and Mary Murphy at the Maharam design studio years back,” Mette continues. “It had pink, orange, and turquoise, and I was like, ‘Why is this not in production, I love it!’ A little while later, I saw a Sofa Compact in the same textile in a museum collection, and it inspired us to link the colors to the Eames Shell Chair. Then we added colors from the HAY palette and ended up with what we have today.”

“It felt like a big ask to touch something that is so untouchable.”—Mette Hay

The resulting collection—eight pieces designed by the Eameses and reconsidered by the Hays— comes to fruition after years of thought, research, and testing. In addition to the expanded color palette, the HAY-selected materials riff on the respect for experimentation inherent in every Eames design: The Eames Hang-It-All, which sports cast-glass balls in place of the original painted wood, and the Eames round occasional and low wire tables with cast-glass tops that can be used indoors and out. Shell chairs are now made of 100% post-industrial recycled plastic. And Maharam has faithfully produced that original, archival colorway of Jacob’s Coat by Alexander Girard for a special version of the Eames Sofa Compact.

Among their favorites are the wire chairs, finished with a matte powder coat that’s graded for outdoor use—following in the tradition of earlier Eames applications. Eames Demetrios, director of the Eames Office and one of the Eameses’ five grandchildren, references the Aluminum Group (1958), which was designed for the J. Irwin Miller house in Columbus, Indiana, and reintroduced by Herman Miller with outdoor finishes in 2011. “I actually think the best outdoor seating is the Eames wire chair, which is why I’m excited about our collaboration,” he says. “You can hose it off! And it’s less expensive than Aluminum Group, also easier to move around.”

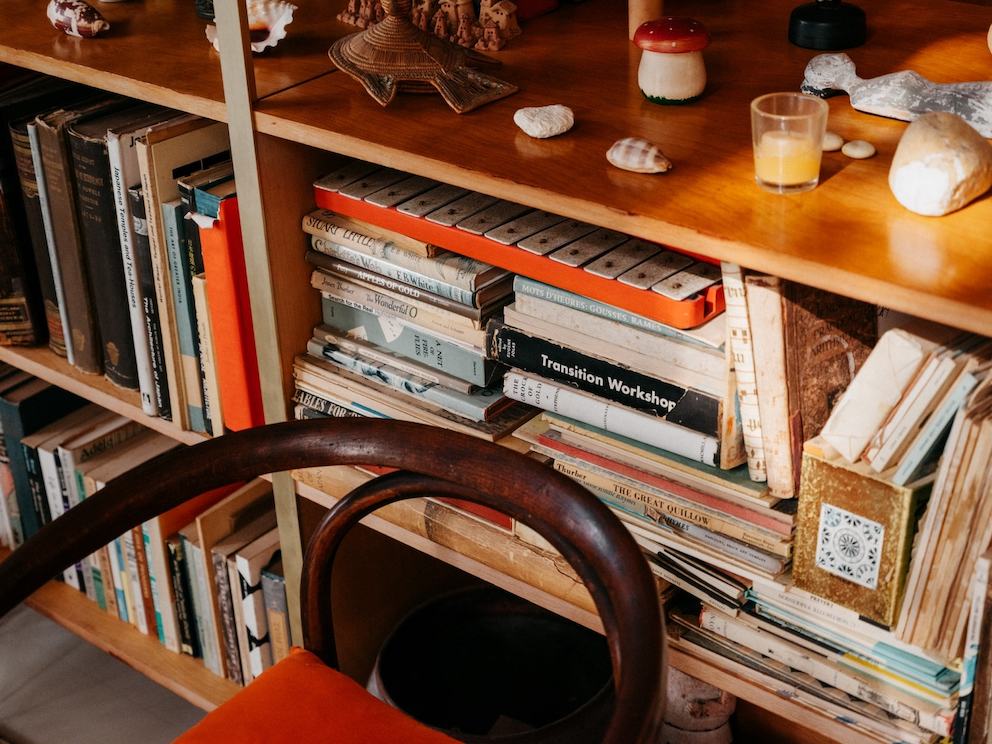

Detail of the distinctive freestanding bookcase/storage unit, one of the central features of the double-height living room in the Eames House that the Eames Office fabricated as a unique prototype 1958. It is stocked with often-referenced books from the Eameses’ personal library as travel artifacts. [Photo by Jake Stangel for Herman Miller, courtesy of Eames Foundation.]

Flash forward to 2022: Mette and Rolf Hay have flown from Copenhagen to Los Angeles to make a pilgrimage to the Eameses’ own home in Pacific Palisades, on a eucalyptus-lined bluff overlooking the Pacific. The house—which was finished in 1949 as No. 8 in a series of influential modern prototypes known as the Case Study Houses—is a crucial artifact in understanding the Eames approach to design: experimenting with it, living with it, incorporating it into an ever-expanding universe of influences.

As Mette and Rolf got the insider’s tour of the residence and studio building from Lucia Atwood, director of the Eames Foundation and another of the Eameses’ grandchildren, and her sibling Eames (Demetrios), they discussed the origins of the Herman Miller x HAY Collection. Read on for their earliest Eames memories, and how both couples live with objects, design in partnership, and draw inspiration from the culture at large.

At left, a detail of the entryway to the famed Eames House, located on a bluff overlooking the ocean in the Pacific Palisades of Los Angeles. The house, which Charles and Ray Eames designed in 1949, is also known as the Case Study House No. 8. At right, a view from the entry into the double-height living room, showing the house’s white tile floor, which was replaced in 2012 as part of the first phase of work in the Eames Foundation’s 250 Year Project.

On learning from the Eames Office

In a sense, the seeds of the joint collaboration were planted over 20 years ago—well before HAY joined Herman Miller Group (now MillerKnoll). “When I started working in the industry,” Rolf explains, “I went to see an Eames exhibition at the Vitra Design Museum, which changed a lot of things in the way I had been looking at design.”

A voracious reader, Rolf had first studied up on classic design from Denmark dating to the 1950s and ‘60s: Børge Mogenson, Arne Jacobsen, Finn Juhl, Hans Wegner. The Danish greats took a complex understanding of wood and cabinetry and translated that craftsmanship to a new era in which workshop met factory. “What was different with the Eameses was, they were driven by creating design for the many, not for the few. New technologies, and producing things like plywood and later fiberglass in an efficient way—really taking advantage of the possibilities in their time,” Rolf says.

At left, a stack of vintage Eames shell chairs in the Eames Office studio onsite. “It’s hard to understand how the colors were in person originally,” Rolf Hay notes. “It doesn’t always translate through photos.” At right, the Hays discuss the origins of the Herman Miller x HAY Collection collaboration.

“I see that the Hays share with the Eameses a real willingness to embrace any logistical, material and systems challenges as an essential part of the design process.”—Eames Demetrios

That 1997 Vitra exhibition—which predated the point when he and Mette decided to strike out in their own with a company that would bring Danish design into the present day—pushed Rolf to start thinking in an Eamesian spirit. Mette confirms: “Charles and Ray Eames have been our biggest inspiration, especially in the way they used colors and were very experimental with their process. And they were having fun! Many furniture companies in Denmark are talking about how many hours it took to craft a chair. At HAY we’re about innovation.”

Acknowledging the Hays’ kinship with his grandparents, Eames says, “There are a number of connections: The first is a great joy and delight in color and its potential to be an integral part of a design. The second, is, naturally, their compelling journey as a married couple with a unified design voice. Then, I think you have to think about the entrepreneurial aspect of both couples—which is not as widely recognized in the Eameses.”

On living with objects

Lucia explains how the contents of their shared home exemplify the couple’s design values: “Both were concerned with the presentation of their home, from how it welcomed visitors to its effortless flow for living and working. As Ray herself said, ‘Almost everything that was ever collected was just because (it was) an example of some facet of design and form. We never collected anything just as collectors, but because something was inherent in the piece that made it seem like a good idea to be looking at,’” she says.

Lucia Atwood, one of five Eames grandchildren and director of Eames Foundation—the entity stewarding the Eames House and its ongoing preservation—pictured with Rolf and Mette Hay on their first visit to the house.

Rolf takes a similar tack with HAY products in his and Mette’s home in Denmark. “It’s very useful to take a new prototype from the factory into a real environment,” he explains. “You see it in passing, and something happens when you’re not forced to look at it. What is this chair capable of? Or is it something you can’t stand looking at after a few weeks? You work very intensely on something, then keep it at home for a few weeks, learn something, and put that knowledge back into the project.”

In fact the Hays, who have long counted the iconoclastic Eames Molded Plywood Chair among their favorite chairs, keep an early prototype of the forest green version they designed for the Herman Miller x HAY Collection in their own living room.

On drawing inspiration from culture at large

Charles and Ray famously collaborated with the intellectual and creative geniuses of their day. Peek into one of the duo’s customized travel itineraries—which were all meticulously typed onto vellum paper and trimmed to fit into Ray’s address book—and you’ll see a who’s who of cultural heavyweights from Saul Steinberg to Alexander Girard to Billy Wilder.

Similarly, HAY’s founders surround themselves in a creative and social circle that has generous overlap with the products they’ve put into the world. “Architecture and culture and arts and innovation and production—these are all subjects you’re bringing into a project,” says Rolf. Recent collaborations include tabletop pieces designed with food artist Laila Gohar, a chess set with graphic designer Clara Von Zwiegbergk, and the reintroduction of 1971 cult classic chairs and tables by Swiss minimalist Bruno Rey. As Mette explains, “It’s much more holistic than drawing inspiration from one thing.”

One thinks of the Eames Office, and the wildly multifaceted projects they undertook: a history of mathematics, experimental films, film scores, speeches, posters, scale models, games and toys, plus a vast archive documenting one-off studio projects, correspondence, documentary photography, and more. As quoted by Daniel Ostroff in his book The Eames Anthology, Eames associate Bill Lacy described their style as a non-style: “only a legacy of problems beautifully and intelligently solved.”

Both Lucia and Eames—who spent time with Charles and Ray as children and young adults—recount how the pair weren’t interested in regaling their grandchildren with tales of their past hits, instead preferring to quiz them on what was compelling and culturally relevant to younger people. Such curiosity kept the Eames Office ahead of even the most cutting edge in design, an industry in which significant change happens over decades, not seasons.

The Hays, too, tend to think of what’s coming rather than codifying what they’ve already done. “We often have this conversation, Is this really HAY? It’s HAY if you feel good about it!” laughs Rolf. “I think it’s OK to change direction. I don’t want HAY to be religious, or too strict about what we can’t do or won’t do. I want us to be open and prepared to approach design from new angles.”

On designing in partnership

Last, but certainly not least, is the relationship at the heart of the Eames lore. Although there’s a tendency to try and ascertain who did what—credit one partner with the furniture design, one with color palettes; laud one partner for successful client pitches, the other for maintaining a robust correspondence with friends and colleagues—Charles and Ray were co-equals. (Another anecdote from the Ostroff book: “In a [1952] speech… Charles explained that Ray preferred to work under the “brand name.” He also mentions that several texts formally attributed to Charles “were actually written in longhand as first drafts by Ray.”)

Lucia says of her grandparents’ relationship, “Sometimes people find it hard to understand how two creatives can work together—that the process improves the output. I loved watching their rapid-fire back and forth at the Eames Office as they considered a next step. Complete respect and trust. Their shared satisfaction upon reaching a decision was inspiring and joy-filled.” That process is undoubtedly one of debate, potential friction, and the exponential effect of having two minds attacking the same problem from different viewpoints. But there’s a philosophical alignment at work, as well.

As Rolf puts it, “When you work as a couple, you work without the gift wrapping. It’s not about how you are presenting an idea, it’s more about what’s inside,” he says. And he would know. While the Hays operate HAY a bit differently than the small but mighty Eames Office of the midcentury, there’s a similar honesty at work. “What’s extremely important to Mette and me is you can share your opinions in an open way.”

Rolf Hay peering through a fish eye set into the glass slider into the house’s kitchen—a repository for Ray Eames’s collections related to her love of entertaining. The off-the-shelf Truscon system Charles and Ray used to build the Eames House did not offer sliding doors, so the Office staff took a window and converted it by adding wheels, a track, and a handle. The fish eye is not original to the 1949 design, but is in step with Eamesian explorations of perception in film (Kaleidoscope), in their house (prisms), and in the Eames Office at 901 Washington (circus mirrors).