The office, as we know it today, was a relatively new concept at the turn of the last century. As new modes of production, creation, interaction, and service evolved the way workers behaved, so too did the landscape of the modern workplace. And it continues to change. As the following selections from our library attest, Herman Miller has been at the forefront of anticipating, shaping, and innovating environments that respond and engage in these cultural phenomena: the how, why, and where of work. These publications underscore a core tenet at Herman Miller: design must solve a problem for people. Researching and understanding the problem comes first, and thoughtful design—whether in the form of an object, an environment, or a company—is the answer.

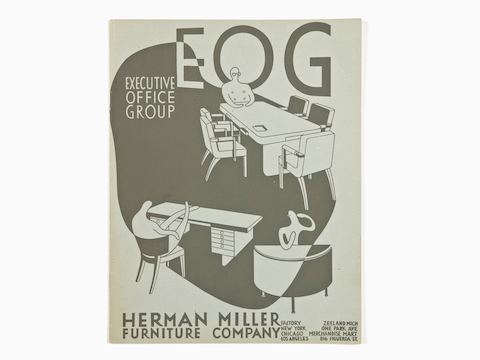

EXECUTIVE OFFICE GROUP

Gilbert Rohde, 1942

Gilbert Rohde spearheaded a paradigmatic shift in Herman Miller’s approach to design in the ’30s. At his behest, the company abandoned its reliance on ornate reproductions and began producing furniture of the day—unembellished, modular pieces designed for modern life and work. The catalogue for Rohde’s Executive Office Group describes his designs as “office furniture that is modern from the inside as well as the outside, modern in the works as well as in the way it looks.” In this sense, the EOG book is as much a manifesto as it is a catalogue of offerings. By encouraging customers to select from over “200 combinations and variations,” Rohde underscored the variety and utility of Herman Miller products. EOG planted the seeds for the human-centred approach to office design that Nelson, Eames, Propst, and Stumpf would continue to refine and redefine, and which Herman Miller continues to uphold.

“This furniture has no escape complex, it looks like what it is and proclaims the clear thinking executive who will have no cobwebs in his business.”

-Gilbert Rohde

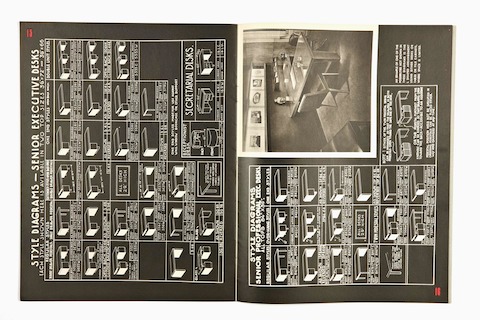

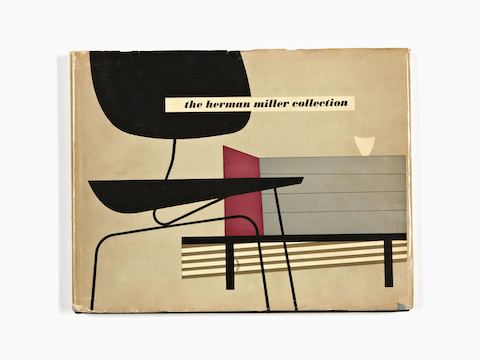

THE HERMAN MILLER COLLECTION

George Nelson, 1952

George Nelson had great things in mind when he set out to produce the first Herman Miller Collection catalogue in 1947—much to the dismay of CEO D.J. De Pree, who rejected the design based on the projected costs. But instead of downgrading, Nelson upped the ante, adding a hardcover and an unheard of three-dollar price tag. The gambit paid off (literally), and the 1948 catalogue set a new standard for the industry. By 1952, Nelson had further honed his approach to honest, problem-solving design. The catalogue’s two chapters dedicated to work further refine his call for furniture that works for both the home or office, noting a contemporary shift toward “workmanlike” residential spaces that are easier to keep up, and the “warmth and informality of the well-appointed home living room” creeping into the office.

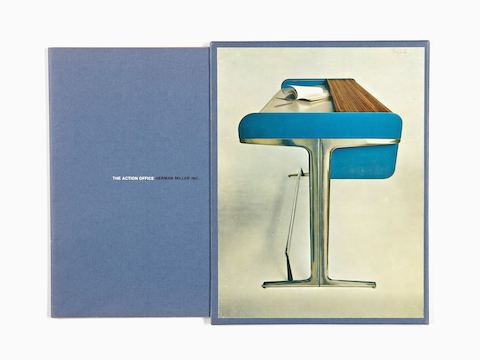

THE ACTION OFFICE

Robert Propst & George Nelson, 1964

By describing the plight of the common office worker George Nelson and Robert Propst argue the insight and aesthetics behind “the Action Office.” Nelson, then Herman Miller’s Design Director, and Propst, its Director of Research, back their position with numerous examples of how Action Office promotes health and productivity: by encouraging people to change postures throughout the day; giving them ways to store and display materials; and allowing for adaptation so furnishings can adjust to the ebb and flow of the workday. It’s only after they establish these criteria that they delineate the products that will bring this workspace to life—by that point, most readers are already sold.

“The office, then, primarily should be a mind-oriented living space.”

-Robert Propst & George Nelson

THE OFFICE: A FACILITY BASED ON CHANGE

Robert Propst, 1968

In this classic treatise, Robert Propst spells out his vision for the modern office. As Herman Miller’s Research Director, Propst’s investigation of “the office and the human performer” asserts that the constant, exponential change in technology and modes of work has left the physical environment lagging far behind. Since the revolution in work was (and still is!) based on communication, Propst argues that networks must be the primary concern. Outlining the principal operations for Action Office 2, Propst states that “almost any space can be upgraded” and allow people to adjust their offices with ease and grace, without imposing large costs or delays. In theory (if not in practice) this new facility would place power in the hands of the people who actually inhabit a workspace.

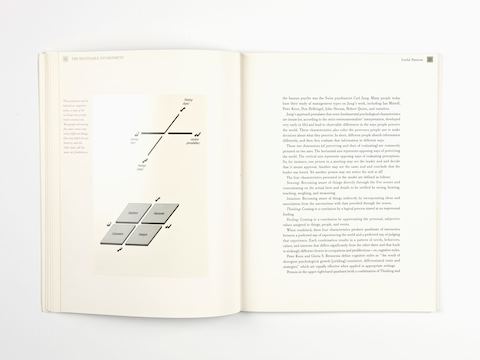

THE NEGOTIABLE ENVIRONMENT: PEOPLE, WHITE-COLLAR WORK, AND THE OFFICE

Cecil Williams, David Armstrong & Clark Malcolm, 1985

The Negotiable Environment takes a decidedly psychoanalytic approach to white-collar work, citing both Freud’s assertion that “man’s goal is to work and to love” and mapping out Jungian behavioural diagnostics as interpreted by Myers-Briggs. It’s an analytic but never pedantic read (save for a number of serious-looking graphs) that explores the highly adaptive and flexible environments required in the face of rapidly changing technological advancements. The takeaway is that we need to create spaces that will “negotiate” our disparate needs and dualistic nature, as well as the conflicting demands of the modern workspace.

“Why shouldn't the office encourage the human will to contribute, produce, and find meaning in work?”

-Cecil Williams, David Armstrong & Clark Malcolm

EVERYBODY’S BUSINESS:

A FUND OF RETRIEVABLE IDEAS FOR HUMANISING LIFE IN THE OFFICE

William Houseman & Clark Malcolm, 1985

Formatted much like a children’s book for adults and peppered with quips like “one person’s Muzak may be another’s torture,” Everybody’s Business can be viewed as the crowd-pleasing companion piece to The Negotiable Environment. This slim book (and inserted abecedarian flip book illustrated by Seymour Chwast) chronicles a variety of traditional and non-traditional workspaces and provides point-counterpoint ruminations on workspaces, from the architecturally ideal office park to the glorified closet. A composite sketch of the white-collar workforce in the mid ’80s emerges. The takeaway is that the quality of an office environment unequivocally affects a person’s ability to perform his job well, and that the health of the overall office environment and culture is, in fact, “everybody’s business.”

BUSINESS AS UNUSUAL: THE PEOPLE AND PRINCIPLES AT HERMAN MILLER

Hugh De Pree, 1986

Hugh De Pree, son of Herman Miller founder D.J. De Pree, served as CEO from 1962 to 1980, and oversaw Herman Miller’s transformation from a moderately successful and celebrated producer of modernist designs, to a publicly held, multi-million dollar, international corporation. Through a series of reminiscences and reflections, De Pree paints a vivid picture of the company’s values and history. "The difference at Herman Miller," he writes, "is the energy beamed from the thousands of unique contributions by people who understand, accept and commit themselves to the idea that they can in fact make a difference." So while there is no shortage of D.J., Nelson, Eames, Girard, Propst, and key employees like Jim Eppinger and Joe Schwartz, De Pree also turns the spotlight to dozens of lesser-known individuals whose achievements, connection, dedication, beliefs, and drive helped forge the idea and reality of Herman Miller.

“People become owners of this business through their ideas, their influence, participation and that portion of their lives they devote to it.”

-Hugh De Pree

LEADERSHIP IS AN ART

Max De Pree, 1987

Leadership Is an Art takes a comprehensive view of organisational leadership. Max De Pree gives us a wonderful picture of Herman Miller’s aspirations as a corporation and community. The philosophy of leadership and human relationships presented is a goal that organisations and individuals around the world have adopted—over a million copies of this book are in print. Through stories and questions, De Pree relates his view of leadership to other dimensions of life at Herman Miller—design, community service, corporate values, and inclusiveness. He tells us “who you want to be” must always come before “what you want to do.” Leadership Is an Art is the most complete statement of the aspirations that have guided Herman Miller to become the company it is today.

SEE MAGAZINE

The New Office Landscape: Why Variety and Choice Are Good for Work Environments

Rick Duffy & Don Goeman, 2004

In the early 2000s, a team of people at Herman Miller began re-evaluating the state of work environments. Their research led them to organisations experimenting with new, increasingly flexible, less traditional kinds of workspaces geared toward interaction, openness, and a mix of tools, furniture, and technology. In 2004, the team published a manifesto calling for “New Office Landscapes,” echoing the work of the Quickborner Group 40 years before and known as burolandschaft (“office landscapes”). Their ideas also draw on the precursor of new urbanism.

“The kind of anonymity found in plain sight at Starbucks, the kind of variable stimulation found in libraries and public plazas—these are the new qualities to be fought for in work environments.”

-Rick Duffy & Don Goeman