In 1978, shortly after Charles Eames’ death, Hugh De Pree asked writer, teacher, and design critic, Ralph Caplan, to address his annual President’s Club meeting on the subject of “Eames and quality.” Originally meant as a “briefing” to precede a corporate visit to the Eames office, De Pree felt Caplan’s words resonated enough to have them reprinted in a small booklet and distributed to the company at large. Today, with more configurations of the Eames Shell Chair available than ever before, Caplan’s words are perhaps more pertinent than ever.

Charles Eames was important to Herman Miller in many ways. One of the most important of them was an insistence on quality in our product and in our approach to whatever we do. No matter how we grow and change as a company, it is essential that we sustain that emphasis.

Last year, in order to look at how quality was achieved in the Eames office I asked Charles and Ray Eames to make a presentation of their work and thought, to be followed by a visit to their incomparable office. Charles died a few weeks before the event was to take place, and Ray Eames, understandably, did not wish to appear.

But with Charles gone it seemed more important than ever that we examine his ideas and ways of working. So I asked Ralph Caplan, who had known Charles well, worked closely with him, and written widely about him, to talk to us about Eames and quality, as a “briefing” for our office visit. Although the occasion was the 1978 meeting of the President’s Club, the remarks that follow are really addressed to all of us at Herman Miller.

Hugh De Pree

President, Herman Miller, Inc.

Quality in the work and thought of Charles Eames is as much action as abstraction: he practiced quality. It is not yet easy to remember to speak of Charles in the past tense, but it is necessary, just as it is necessary that we keep his concern for quality in the present tense. Hugh De Pree says, “In recent years Charles and I did not talk much about design, but we talked about the necessity of maintaining quality as the company grew larger. Charles kept asking me if people at Herman Miller were aware of this necessity.”

The question can be raised in his absence. What the Eames office designed for Herman Miller, the company can go on making: one way to honor him now is by making it as well as he always wanted it made. (It was, after all, Charles who identified Herman Miller as a producer of “good goods.”) But a better way to honor him, and in the long run to honor yourselves, would be to apply what you have learned from him to whatever the company makes and does.

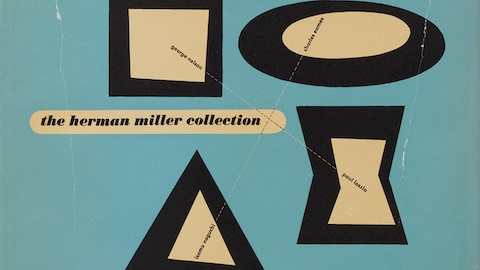

That implies an unusual role for a designer – dead or alive – but not an unusual one at Herman Miller, where designers were from the very beginning perceived as teachers. I don’t know of another company anywhere that has used designers in quite this way, and it started with founder D.J. De Pree. When D.J. today talks about Gilbert Rohde, he refers to “all the wonderful things he was teaching me.” George Nelson also was from the first recognized and used as a teacher, as he still is today. Now that Charles is dead, it is fitting to look for his legacy in teaching rather than in hardware. The chairs and seating will endure only as long as Herman Miller makes them, as long as they are preserved, as long as other companies copy them. The teaching, on the other hand, can’t be preserved as such. It has to be assimilated and acted on. And because that requires intelligence, courage, sensitivity, and faith, it is guaranteed safe from copiers.

Some of you are worried about a corporate identity crisis. Statistically, there is good reason to worry. More than 60 percent of your people are new, having been here less than two years. “These people don’t know who we are,” I am told. “They don’t know our history.”

I understand the problem, but there’s a hazard in addressing it. Casey Stengel once startled a visitor to the Mets locker room with the remark, “We was just reminiscing about tomorrow’s game.” As with many of Stengel’s funniest lines, it is absurd in a way we recognize as applicable to reality: reminiscence can be one of life’s more rewarding pleasures, as long as we keep it out of tomorrow’s game. The past is a nice place to visit but we wouldn’t want to live there.

In the silent movie called “Silent Movie,” Mel Brooks plays a has-been film producer who is challenged by a guard on the MGM lot. “Don’t you know who I used to be?” he asks indignantly. Within Herman Miller I see an understandable but distracting concern with “who you used to be.” Corporate memories become as clouded as any other kind, in a way not peculiar to Herman Miller. When I was in the Marine Corps, veteran Marines, bemoaning the terrible changes in how things were done, spoke lovingly about “the old Marine Corps,” which they remembered as having been peopled entirely by heroes. A friend of mine used to mutter cynically, “The old Marine Corps ‘that will never be the same again’ – and never was.”

To be sure, a company growing so fast that newcomers are in the majority has grounds for concern. Your people do need to know the background of the remarkable enterprise called Herman Miller, but what exactly is it they need to know? Significant dates? I doubt it. The legends? Not everyone here agrees on the legends. Not everyone here agrees on even the simplest facts of corporate history. Anyway, all corporations have histories. Setting the record straight is less important than getting the direction straight. It is important for new people to know what makes Herman Miller unique now, because that is what will keep it unique, however much the line or the competition changes. The uniqueness lies to a great extent in the company’s relationship with designers and in its consequent approach to quality.

On the campus of Antioch College there is a building donated by the inventor Charles Kettering. It bears my favorite memorial plaque inscription: “This building is not a monument. It is a workplace.” If we are looking for an Eames memorial, the clue is in the work.

Work, as Kettering indicated, takes place in a workplace. For Eames the place is an old garage, with an industrial anonymity distinguished on the outside only by the neat numerals.

But on the inside there is anything but anonymity. You enter a building by some abandoned railroad tracks in a slum and encounter an environment so rich in artifacts, so pleasurable in ambience, so full of wonders and surprises, so thoroughly equipped for work and play as to be a kind of inland treasure island. The common denominator is the abundance of what Charles credited Herman Miller with: “good goods.” Everything the eye rests on is absolutely first rate, and everyone in the place is engaged in the kind of activity that makes stuff first rate. So the Eames office serves simultaneously as an object lesson in quality and a demonstration of how quality happens.

A simple office map – an abstraction of all these activities – would reveal a number of things about the office. For one thing, although it is like no other office in the world, it is an office. Charles – unlike many designers who were far more businesslike than he – never found the idea of business unappealing. He called his clients customers. And he called his workplace an office, never a studio or an atelier.

Charles always referred disparagingly to the building he spent most of his life in for 33 years as a “nonsolution.” It is. But it is a nonsolution demonstrably superior to most solutions.

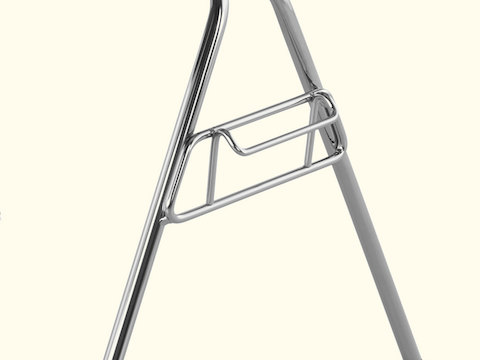

Central to the main work area is the model area. Nothing is more important than this placement, for nothing in the Eames office is more important than models.

Theirs is not the conventional way of using and viewing a model. Models are usually cute, idealized miniaturizations of the real thing. Their purpose is to show the client, who presumably cannot read plans, what the final project will look like. But what they usually show is what the project would look like only if people were to behave the way architects wish they would. Models of this kind are not appreciably different from the models children make with kits. Frequently they are treated as aesthetic objects. Some architectural offices have “model rooms” to which clients are brought for visiting, as if the model were an invalid aunt. Sometimes models go directly from the model shop to the client’s reception area, where they are displayed as a three-dimensional artist’s rendering of things to come.

“Again and again Eames demonstrated in his work that quality was not an article of faith, but an operation – something you labored at.”

- Ralph Caplan

Eames office models are always designed with something else in mind. Their point is not to paint a pretty picture of the future, but to test-drive it.

Anyone engaged in a creative act understands the necessity of risking failure. The fear of making mistakes is a great inhibitor, but the willingness to fail must include the willingness to anticipate failure in advance, in order to try to avoid it. This is one use for the models in design and in everything else: the model is a projective device. Eames office models are, like scientific models, instruments of discovery, working tools. By manipulating them you could begin to figure out what would work and what would not; and, of course, you could also show the client what to expect, and with utter realism.

The realism of Eames models has always been astonishing. They look as much like the real thing as can be imagined and built, and are inhabited by figures constructed from a continually refreshed supply of photographs of people in various positions. But the verisimilitude is functional: Eames exhibit models are the first ones I have seen that acknowledge the possibility of uneven traffic patterns, bored viewers, unpopular exhibits.

No matter how real the model looks, there is an essential difference between prototype and product. The aim of the prototype is to become the product, not to be the product. In manufacturing – as in design – there is a terrible danger in confusing the two, in shipping prototypes as if they were products.

A growing company in a highly competitive industry is pressed to do just that, but so are designers, writers, boxing managers. It is axiomatic that, if you bring along a promising welterweight too fast, he will never develop into either a fulfilled welterweight or a promising middleweight. Charles never yielded to these particular pressures, and a well-used model was one means of resisting them.

This is not to say there were no deadlines to meet. There almost always were. But deadlines, like other constraints, were never to become excuses for inferior work. When describing the speaker he designed for Stephens Trusonic, Charles explained, “It was a matter of the best you could do between now and Tuesday.” However he was quick to add that “The best you could do between now and Tuesday is still a kind of best you can do.”

As Peter Pearce has written, “Eames’s work was always as good as it could be, and the standards of quality he established must become the standards to which we all aspire.” That suggests a useful, if very simple, definition of quality – to do work that is “as good as it could be.”

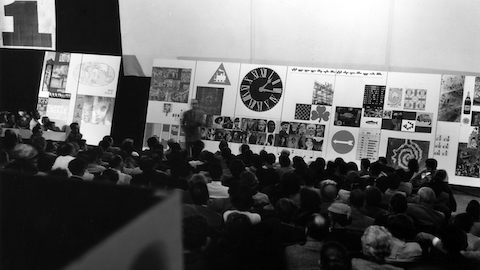

The operative standard of quality in the Eames office puts pressure on the people who work there. But even people who don’t work there, work there; for visitors are assimilated into the work process to keep them from becoming distractions. They become distractions anyway. Here is a note I made 15 years ago:

“In the same shop, and at the same time, members of the Eames staff are drafting, sawing, sewing, drawing, welding, photographing, editing film, directing actors, auditioning actors, eating, reading, writing, and above all talking – talking to clients, physicists, materials experts, mathematicians, writers, production foremen, architects from the Saarinen office, visitors. Curious visitors. Celebrity visitors. Announced visitors. Unannounced visitors. Too many…”

Quality in an office results from responsibility that is shared rather than simply parceled out. Perhaps there is a clue in the concept of “ownership” common to Eames and Herman Miller. Charles was fond of quoting from a John Gardner novel in which a lunch counter customer complains about the quality of a sandwich and the counterman replies defensively, “I only work here.”

“Somebody around here better act as if he owned the place,” the customer says.

While everyone around the Eames office, even casual visitors, acted at times as if they owned the place, there was never any question of who ultimately took ownership of the problems. One member of the Eames staff used to drive people crazy by looking over their shoulders as they worked and asking them very quietly, “Does Charles know you’re doing it that way?”

As a gamesmanship ploy that seems to me quite marvelous. But what makes the gamesmanship possible in the first place is the assumption of quality. One might ask how different Herman Miller would be if enough people periodically asked, “Does Charles know we’re doing it that way?” As an exercise, try substitution other names for Charles’s and see whether the question remains convincing as a reminder of quality.

While that might be a useful exercise, it can also be a horrendous one. Such a big-brother-is-watching-you question could inhibit the flow of ideas or of almost anything else. What would have horrified Eames is the suggestion that there is an a a priori “right away.” Charles himself thought in such terms only lightly and only after the fact. Quality was for him, among other things, something the absence of which would embarrass you. “When we do a product,” Eames used to say, “we ask, ‘what would Bucky think?’ And when we are doing graphics, we ask ‘what would Paul Rand think?’”

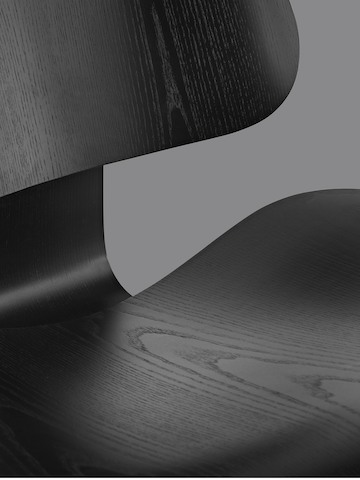

Nowhere is the Eames attitude toward quality more evident than in his treatment of art. What does art have to do with quality in manufacturing? Well, consider such disparate Eames films as “Cezanne” and “The Fiberglass Chairs.” That the same intelligence produced both films is clear not just because of the similarities of color and texture, but because of an attitude toward objects that embraces both paintings and chairs. Both films are art films, and both document quality as process. “The Fiberglass Chairs” is one of the finest industrial films ever made, and perhaps one of the most sensuous films of any kind ever made. It takes the viewer into the realm of ownership that goes beyond possession to understanding. The chairs are characters in a much more convincing way than in, say, Norman McLaren’s “Chairy Tale” or Mel Brooks’s “The Twelve Chairs.” Both “The Fiberglass Chairs” and “Cezanne” are about art as Charles understood it, which is not precisely the way most people in the arts (or anywhere else, for that matter) understood it.

Eames cared very deeply about painting and sculpture and music, but his concern was art was neither limited to, nor very often directed to, those formal modes. Sometimes it stood in direct opposition to them. He thought, for example, that the CBS building in New York was splendid corporate art but believed that on the inside the art had been relinquished to fine art hung on the walls.

Because art was an attitude that could infuse any worthwhile activity, Charles was dedicated to what he called “taking pleasure seriously.” There was nothing he was more serious about than pleasure, and nothing he found more pleasurable than the high seriousness of art and design and science and work and play.

You see, Eames thought art had to do with what you did, rather than what you bought or hung or looked at in museums. Art was the first-hand experience of quality. So when consulted by MIT on how to introduce more art into their scientific and technological curricula, he rejected the idea of fine art courses. Instead he proposed that each MIT academic department include teaching assistants who not only knew physics, mathematics, or other departmental disciplines, but were also trained in film, graphics, and writing. Their role would be to prepare packets of information telling people what was going on in their field. The best of those packets would be distributed throughout the university and the best of those would be distributed outside the university. Moreover, the packets were intended to “arrive at insight, not just to convey it.”

The second part of the scheme required each student to teach something of his or her major specialty to an elementary school class. This teaching could be in the form of film, exhibit, lecture, games, models, or whatever. “If the MIT student is going to learn anything about art,” Eames said, “he will learn it here and not through any aesthetic vitamin concentrate.”

“Quality in an organization depends on responsibility that is shared rather than simply parceled out. This concept of “problem ownership” is common to Eames and Herman Miller.”

- Ralph Caplan

What did he mean? He seems to have meant that art consisted of doing something communicative uniquely well. Art, in other words, was realizing the best of yourself, and then sharing it. Sharing it was not necessarily art. Neither was excellence, until it had been shaped into a form that let you share it with someone. Quality, then, was a matter not only of how well you did something, but of how well you were able to communicate it.

Again and again Eames demonstrated in his work that quality was not an article of faith, but an operation – something you labored at. Not always satisfactorily. Eames was, to take liberties with Reinhold Niebuhr, a perfectionist in an imperfect world. Because he was a perfectionist, he was doomed to chronic frustration: because he was a genius, he was able to realize a great many small perfections. So far in history small perfections are the only kind it has been given us to achieve.

Genius is not merely an infinite capacity for taking pains, but certainly the fruition of genius requires such a capacity. And taking pains can help make up for the lack of genius.

With Charles, though, taking pains was a way of professional life, something you did out of respect for the work and ultimately for yourself. This attitude was rooted in his understanding of art, which is why he distrusted “self expression” as an artistic mode, and why he did not find the artistic impulse inconsistent with professional, or even business, life. He saw room for art in business practice. This was never meant in the cheap sense – do not confuse Eames with the character in Babbit who thought advertising jingles were high art. Eames never confused the form of poetry with poetry. Rather, for him, the art resided in the quality of doing. Taking pains was part of this, and served to remind us that the process is not magic.

That the process is not magic is an old Eames lesson. For Herman Miller, this is where you came in. When Eero Saarinen and Eames won the Museum of Modern Art chair competition, they were asked about the trick of winning competitions. Eames admitted that there was a trick and decided to reveal the secret to anybody who wanted it. Here it is in his own words.

“This is the trick, I give it to you, you can use it. We looked at the program and divided it into the essential elements, which turned out to be thirty odd. And we proceeded methodically to make one hundred studies of each element. At the end of the hundred studies we tried to get the solution for that element that suited the thing best, and then set that up as a standard below which we would not fall in the final scheme. Then we proceeded to break down all logical combinations of these elements, trying to not erode the quality that we had gained in the best of the hundred single elements; and then we took those elements and began to search for the logical combinations of combinations, and several of such stages before we even began to consider a plan. And at that point, when we felt we’d gone far enough to consider a plan, worked out study after study and on into the other aspects of the detail and the presentation.

“It went on, it was sort of a brutal thing, and at the end of this period, it was a two-stage competition and sure enough we were in the second stage. Now you have to start; what do you do? We reorganized all elements, but this time, with a little bit more experience, chose the elements in a different way, (still had about 26, 28, or 30) and proceeded: we made 100 studies of every element; we took every logical group of elements and studied those together in a way that would not fall below the standard that we had set. And went right on down the procedure. And at the end of that time, before the second competition drawings went in, we really wept, it looked so idiotically simple we thought we’d sort of blown the whole bit. And won the competition. This is the secret and you can apply it.”

That was Eero’s trick. For some people it is as hard to understand as a sleight-of-hand trick. The point is not that quality is attained by the simple expedient of keeping your nose to the grindstone, but that the details are no less interesting, no less important, no less demanding of creativity than any other part of the process. Remember that it is in a Herman Miller film that Charles, doing his own narration, declared, “The details are not details. They make the product…It will in the end be these details that…give the product its life.”

In the course of a long relationship, clients and designers invariably do things to irritate each other. Charles certainly had professional habits that were irritating to clients, and he in turn, was irritated by his clients, including this one. A minor but interesting source of irritation with Herman Miller was the company’s emphasis on innovation. Charles distrusted it. He did not distrust innovation in itself; there were times when, if you were able to, you had to innovate. But to set out to innovate was, he felt, to introduce a distraction from quality, for the proper emphasis was not on making things new but on making them good. Making new good things, or making new things good, was something you did by solving problems of substance, not by searching for novelty.

For example, a major brewery once asked Eames if he would be interested in taking on the redesign of their beer label. He was intrigued: normally people didn’t turn to him for package design. After careful consideration of the existing label, however, Eames concluded that there was no way of improving it, and he recommended that the client save the design fee and put the money into engraving the label rather than printing it. (They did save the design fee; they did not engrave the label.)

What the client was after was clear: innovation. What Eames was after was just as clear: a qualitative improvement without arbitrary change.

Consider “Clown Face” – another film that may appear to be remote from your business but is not. It was not designed for you; it was designed as a training film for Ringling Brothers, Barnum & Bailey clowns. It deals with discipline, with constraints, with tradition, with the freedom from any pressure to innovate, with taking pleasure seriously, with quality. Therefore, it was designed for you.

This simple, relentless study of a clown putting on his makeup while the show goes on outside his dressing room dramatizes the unity of quality, which is not achieved by compartmentalizing the work process. We tend to divorce the conceptual from the menial, idea from execution; but performance has to include all stages of the process. Quality means that details are not boring, and what keeps them from being boring is the steadily increased depth of performance.

Ever since his death, people both within Herman Miller and outside the company have been asking, “What is Herman Miller going to do about Charles Eames?” Personally, I become impatient with the question. Why the insistence on doing something when there is nothing to be done? But I am wrong and they are right; their concern is valid, and my impatience is petulant. There must be, for all our sakes, some formal acknowledgement of the fact of his death and the significance of his life.

In the meantime, though, I return to the point I began with: The finest tribute is the commitment to quality. So that when people ask, “How is Herman Miller going to honor Charles Eames? You can say, “We are already doing it.”

“The finest tribute is the commitment to quality.”

- Ralph Caplan