I first visited Irving Harper in the spring of 2012. I was interviewing him for a film about his work. He was 96 years old.

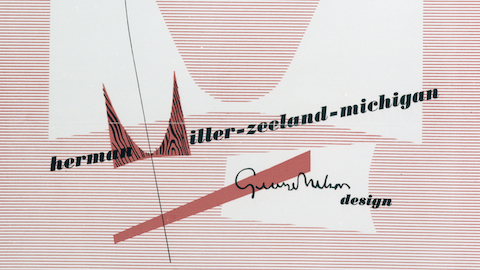

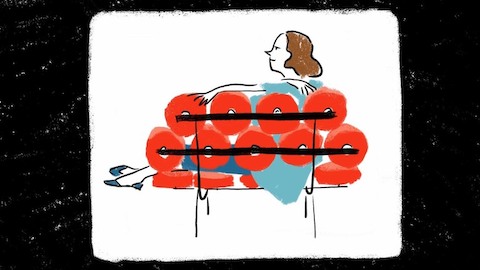

As design director for the Nelson Office, Harper was responsible for some of the most compelling and iconic designs of the twentieth century—from the Marshmallow sofa, to the Ball clock, to the Herman Miller logo itself. Remarkably, his Herman Miller history goes back even further than Nelson, to the office of Gilbert Rohde, where he worked as a draftsman before World War II. And somewhat unbelievably, here he was before me, sitting quietly in his favorite chair reading a book.

Toward the end of his tenure with Nelson, Harper began making paper sculptures in his off hours to relieve stress—at the time he was the design lead on a massive project, the Chrysler Pavilion for the 1964 New York World’s Fair. It was a hobby that continued from 1963 to 2000, during which time Harper created the roughly 500 sculptures that besiege almost every surface of his 3-story home and barn. It may have taken him some 40 years to accumulate that collection—meticulously cutting, folding, and gluing—however, as a visitor it all hits you at once, as if being struck by a lightning flash of creativity, skill, color, and vision. The word genius comes to mind—although, as I learned, Irving was far too self-effacing to accommodate that sort of compliment.

Completed in 2000, the Owl is the last of Harper’s near 500 pieces.

The living room’s banquet is completely covered in work.

For those familiar with, and fond of, Harper’s design works—his particularly cogent synthesis of industrial precision and idiosyncratic whimsy—discovering the paper sculptures is something like finding a treasure trove of unpublished works by a favorite author. When we made our film they were still relatively unknown; he made them for his own pleasure, and they were still serving that purpose alone. Thankfully for the rest of us, that dynamic has since shifted. Michael Maharam produced an amazing record of the work in the form of a monograph, Irving Harper Works In Paper, and last fall the Rye Arts Center put together the first public exhibition of his sculptures, Irving Harper: A Mid-Century Mind At Play. It was clear that these were both hugely meaningful acts of recognition for the designer who preferred to do the creative work out of the spotlight.

Each time I visited Irving, I would find him reading in that same chair. He always seemed happy to have guests and would get upset that his memory wasn’t better. Generally after some prompt he would get talking and wind up telling a great story. His sharp wit was still strong at age 99. He recently joked that he made the Herman Miller logo red because he was a secret communist. (Actually, he just liked the color.)

On our last visit we found a box of Herman Miller-related drawings and blueprints in Harper’s attic and brought them downstairs to share with him. He pored over each one he was handed, taking a moment to reacquaint himself and then scrutinizing every detail. It was apparent that he was enjoying handling these blueprints again. His fingers traced familiar arcs—a result of a lifetime spent at the drafting table.

While a life can’t be committed to paper, Irving Harper certainly gave it a valiant effort! His place in design history, and in the hearts and minds of those he worked with at Herman Miller, is assured. We’ll all miss you, Irving.

“I feel incredibly fortunate to have come upon this deeply accomplished and remarkably obscure 83 year old of such bright, genteel and cogent character in 1999, and to have witnessed his much belated and well deserved recognition since.”

-Michael Maharam

Amazingly, Harper’s sculptures were never executed from a plan.

French curves and scissors—all the tools he needed.

The influence of African art is readily apparent.

A bird of prey’s plumage comes close to realism.

The range of subjects undertaken in the work is breathtaking.

A cluster of abstract pieces hint at some of Harper’s commercial designs.

Almost every available bit of space is given over to Harper’s constructions.

Harper’s workspace looks much the same after decades of use.

A small barn is filled with yet more artwork—much of it quite large.