Design

Why Design, Irving Harper

Irving Harper took paper in a totally different direction.

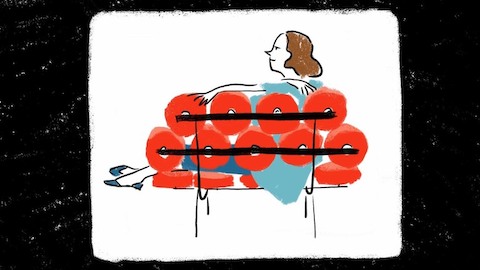

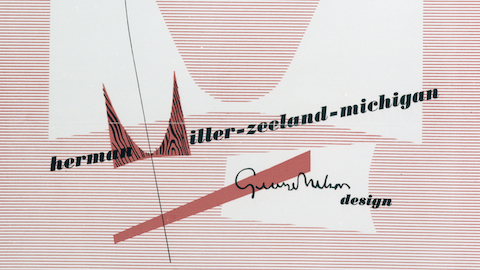

Known professionally for his iconic contributions to the George Nelson office, including the 1949 Ball Clock, the Herman Miller logo, and the 1956 Marshmallow sofa, Irving Harper’s sculptures have never before been shared publicly. Curated by Katharine Dufault and Jeff Taylor, the exhibit opens Sunday, September 14, 2014, with a reception in The Rye Arts Center Gallery, 1:00-3:00 pm, and runs through November 8, 2014. The following essay is excerpted from Irving Harper: Works in Paper (Rizzoli, 2013) and is accompanied by our WHY DESIGN video profile of Irving Harper at his home in Rye, New York.

In 1963, Irving Harper, director of design at George Nelson Associates and author of several of the twentieth century’s most evocative household artifacts, including the atom-like Ball Clock (1949) and festive Marshmallow Sofa (1956), was a nervous wreck. He had been put in charge of the team designing the Chrysler pavilion for the 1964 New York World’s Fair, and he was coping with an ambitious program, a tight schedule, and high expectations.

Four years before, the Nelson office had worked on a monumental exhibition in Moscow for the United States Information Agency. That show, of which Nelson was creative director, included a jungle gym filled with American consumer products and a model home in which Nixon and Khrushchev wrestled for cultural supremacy in their infamous “Kitchen Debate.” Harper’s contributions were minimal; he took care of the rest of Nelson’s clients while much of the office, which had expanded to meet the demand, poured its energies into demonstrating the wonders of capitalism. Now, once again, Nelson had been recruited to promote American industrial power, and this time on American turf—the very place in Queens where the 1939 World’s Fair had ushered in modernity.

Harper disliked the giant stainless-steel globe in Flushing Meadows Park that occupied the place where the Trylon and Perisphere, symbols of the ’39 Fair, once stood. He had been one of five signatories of a telegram sent jointly to President John Kennedy and New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller in 1961 that complained that the distinctly unmodern symbol, known as the Unisphere, “is probably one of the most uninspired designs we have ever seen,” one that threatened to “reflect seriously against United States prestige.”

Located between Ford and General Motors, the Chrysler pavilion was anything but banal. Harper’s design required that the site be flooded and divided into islands linked by bridges. Each island represented a different facet of car making—design, engineering, production—and had a singular feature: a gigantic walk-in engine with pistons shaped like monster heads that pumped up and down and sent off showers of sparks; a garden of auto parts; a rocket signifying Chrysler’s contributions to the space program. Visitors were guided by automatic chair through the entire production sequence. Almost fifty years later, Harper recalled the pavilion as a “wonderful project.” But he conceded that it almost drove him to knit.

“Almost fifty years later, Harper recalled the [Chrysler] pavilion as a ‘wonderful project.’ But he conceded that it almost drove him to knit.”

Harper was looking for an activity to take his mind off the stress—something repetitive and soothing he could do at home in the evening. He considered taking up knitting or crocheting, but he also excelled at building cardboard models for client presentations. One day, he split apart a bamboo window blind and used Duco Cement to reconstitute the matchstick-size pieces into a flowing mask, which he set on a carved wood pedestal.

For the next four decades, Harper made sculptures. He built them mostly out of paperboard, but also balsa wood, beads, straws, toothpicks, pinecones, telephone wire, twigs, dolls’ limbs and glass eyeballs, Mylar sheets, Styrofoam lumps, and pieces of the ceramic clocks he designed for the Michigan-based company Howard Miller. He scouted Manhattan art galleries and the Metropolitan Museum of Art for inspiration and fashioned Egyptian cats and stylized antelope heads, Byzantine towers, African masks, a Renaissance Florentine church in relief. He built constructions stacked like molecules, and abstractions that peeled off the picture plane like a grid of flames. He worked in the styles of Surrealism and de Stijl and made study after study of Picasso, the artist he admired above all others. On his shelves, Guernica’s suffering humans and horses mingled with crows, antelopes, and throned Egyptian animal gods.

Nineteen sixty-three, his year of agita, was also the year in which Harper left the Nelson office, where he had been working since 1947, and went out on his own. He disliked the hustle of running his own business and soon formed a partnership with a fellow Nelson alumnus, Philip George, designing primarily interiors for such clients as Braniff International Airways and Hallmark Cards. When Harper retired, in 1983, his sculpture output stepped up. By the time he had built his last work, around 2000—a glass-eyed owl sheathed in brown paperboard feathers—the collection approached some three hundred pieces. Harper stopped making art, he insists, because he ran out of room to display it in the old farmhouse in Rye, New York, where he had been living for half a century.

Harper still lives in that house, surrounded by those pieces, in a gesamtkunstwerk of which he, at ninety-six, is not only the creator but also a central, vital component. Individually, the sculptures can be appreciated for their charming translations of art historical masterpieces, their structural ingenuity, or their deft expressions of color. They are arresting down to the hinge, piercing, or loop. Collectively, they form a sumptuous catalogue of one man’s perambulations along the boulevards of twentieth-century aesthetics. Arranged in simple, bright rooms among primitive artworks and contemporary furniture—much of which are Harper’s own prototypes—they testify to the playfulness and omnivorous cultural appetites of the era’s great modernist designers. No less than the Eames House, the Harper interior is eclectic. Permeated with a calm sense of artistic adventure, it reflects lives joyfully lived.

In 1960, the Times published Harper’s home in Rye with the headline: “Modern Furnishings Adapt Roomy Old House to Young Family’s Living.” Irving and [his wife] Belle had bought the three-story shingled farmhouse, built in 1895, after outgrowing their small apartment on Jane Street in Greenwich Village. They moved there in 1954, when [their daughter] Elizabeth was one. The Harpers looked in Westchester County, north of Manhattan, because it was on the way to their weekend home in Pawling, New York, and chose the house on Brevoort Lane because it stood on nearly an acre of land, in the shelter of a magnificent beech tree. (Today, Harper’s drawing of the tree is propped up in his front hall—the only artwork displayed among his large, colorful collection that offers a clue to his drafting skills.)

“Individually, the sculptures can be appreciated for their charming translations of art historical masterpieces... they form a sumptuous catalogue of one man’s perambulations along the boulevards of twentieth-century aesthetics.”

- Julie Lasky

“I came here and saw this place and said, ‘This is where I’m going to die,’” he says. He tore down a wall of the sun porch to enlarge and brighten the living room. Beneath the expanse of windows, he built a long wooden shelf wrapping around two sides of the room. “I had to do something with it,” he says of the shelf. “I put plants there at first”—a row of pots with long, leafy fingers is visible in the Times article—“but the plant shelf became smaller and the art became bigger.” Today, that shelf is a place of honor for Harper’s sculptures. It holds his first and last creations—the mask from 1963 and the owl from the turn of the millennium—along with an angel in a cloud of toothpicks and tiny pinecones, a cluster of Picasso-esque figures, a rhinoceros with Mylar armor, and antiquities and art pieces produced by other hands. Works carefully placed throughout the rest of the house—as well as those that became damaged through the effects of time on fragile paper and were retired to the barn at the back of Harper’s property—reveal his waves of interest. A series of masks with sharply angled features tip viewers off to his passion for African art. “I saw things at the Metropolitan Museum’s African collection and thought I’d love to have one for myself, but I knew it would be out of my reach,” he explains. Wall pieces with fields of lavender, green, and gold paper dots tacked to the picture surface have the shimmering effect of Impressionist paintings. Balsa wood sculptures range from desktop models to large, delicate scaffolds flagged with colored paper and preserved in Plexiglas boxes. Animals and birds interested him because of their variety of shapes—“One thing you don’t have with human beings,” he says.

Elizabeth notes that Harper’s Surrealist phase began when she was “a kid and growing out of my dolls and putting them aside. Originally, he would use arms and legs and heads and do stuff with them, but then he liked the eyes. Eventually he ran out of the eyes of my dolls and he started buying them wholesale. I used to carry them around with me.”

“I’d be on a roll with a certain kind of design,” Harper says. “I’d have a sort of rough mental picture of what I wanted to do.” New ideas came from working out structural problems or from seeing a concept at an exhibition that could be translated to paper. “I would get ideas from the gallery but I wouldn’t make drawings. I’d just get started.” He only regretted not being able to install outdoor sculptures on his roomy property. One attempt, a large bird built with exterior-grade plywood that he hung from a tree, disintegrated, he insists, “partially because I didn’t build it properly. I was a lousy craftsman.”

“I’d have a sort of rough mental picture of what I wanted to do... I would get ideas from the gallery but I wouldn’t make drawings. I’d just get started.”

- Irving Harper

Harper rarely showed the sculptures outside of his home. They appeared in a group exhibition in SoHo, at a solo show upstate in Rochester, and in an event staged in his barn. When a sculpture broke while on loan in nearby New Rochelle, he spurned every subsequent request to exhibit the works. Friends considered it the highest honor when he agreed to part with one as a gift, a gesture he indulged in only after years of steady production. A woman who saw the SoHo show was interested in buying a piece; Elizabeth communicated the message to Harper, who had declined to attend the opening. How much would he charge? Elizabeth asked. “How much would a Modigliani sell for?” Harper returned. (Suffice it to say, more than the potential buyer was willing to spend.)

“I never sold any of my pieces,” Harper says today. “I had all the money I wanted. Then I would have lost my sculptures and just had more money. I just wanted to have them around.”

Belle died on December 22, 2009, after sixty-nine years of marriage. Today, Harper lives alone in his art-filled house. The third-floor studio looks untouched from the days when he meticulously assembled his sculptures, not because he was a patient man, acquaintances say, but because he was mesmerized by a ritualistic craft that also required imaginative problem solving. A reproduction of Guernica is tacked to a slanting wall, near a composition by Harper that has similar elements—contorted positions, Cubist perspective, a dynamic mass of figures and abstractions. A photo of a young Elizabeth playing the violin is posted above a picture of Irving in his late thirties or early forties. He has thick, dark eyebrows and a crewneck shirt and looks somewhat strained and bemused and more like George H. W. Bush than Columbo.

“It’s amazing that I don’t have the slightest desire to do them anymore,” he says in his light-flooded living room, where he spends most of his time reading, listening to music, and appreciating his handwork. He recently recalled for [WHY] the days before he had turned the room into a modernist tableau. “I remember I had a circular saw in the living room, and I was building this counter around the room, and I was living here for the time being. I didn’t have any things on my own to decorate it with and hadn’t bought any accessories. So George [Nelson] came by and he looked at all these blank spaces and this blank counter and said, ‘There’s nothing here.’ I don’t know if he meant that as a form of flattery. I rather doubt it. Too bad he can’t come by and take a look at it now.”

“I never sold any of my pieces, I had all the money I wanted. Then I would have lost my sculptures and just had more money. I just wanted to have them around.”

- Irving Harper