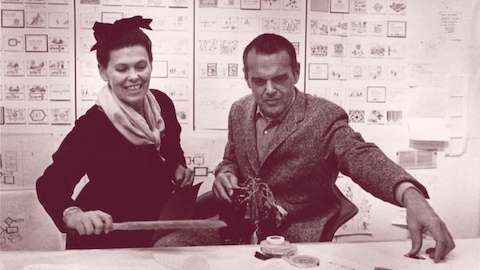

In our second installment of WHY’s design interview series, Design Q & A, we turn to Dutch polymaths Scholten & Baijings. We put the questions of Charles and Ray Eames’ famous interview from 1969 for the exhibition Qu’est-ce que le design? (What Is Design?) at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, to the husband-and-wife team to see what’s changed in the last 49 years.

For nearly 20 years, designers Stefan Scholten and Carole Baijings have worked collaboratively across disciplines, designing everything from furniture and textiles to exhibitions and graphics. The pair begins the process for each new design with a simple mandate: to contribute something to the world that is original, useful, and desirable. Behind their elegantly-designed products is a practice steeped in intensive materials exploration and study. By manufacturing models and materials to their own specifications, and custom-blending hues to satisfy their keen sense of color, Scholten and Baijings marry an atelier approach with the capabilities of mass production to prove there’s a place for craft within industry.

What is your definition of design?

Carole Baijings: The art of designing a product for daily use.

Is design an expression of art?

CB: We are, first and foremost, designers who think that functionality is just as important as the beauty of the product. Even though it might appear that we work like artists by investing a lot of time in studying it and making hands-on models, we are designers and not artists.

Is design a craft for industrial purposes?

Stefan Scholten: We work on a craft method to get shape and proportion and color, but we don’t see design as a craft in itself.

What are the boundaries of design?

SS: For us, there are no boundaries. There are always new technologies, like 3D printing, new materials, or new design directions like well-being, or leisure. Design is always changing and renewing itself.

Is design a discipline that concerns itself with only one part of the environment?

CB: Design is used for every part of life. Almost everything is possible.

Is it a method of general expression?

CB: For us, it is very personal, authentic, and imaginary.

Is design the creation of an individual?

CB: We work as a male-female team. Our team shares the same passion, because it’s this combination of the masculine and feminine, intuition and creativity, that makes for difference and results in successful products.

Is design a creation of a group?

CB: Because we have a team, we always say that we want everyone to want the new products. If we don’t want them, then we don’t do them. Why design something we would not use ourselves?

Is there a design ethic?

CB: We always make our own models, colors, and materials. By doing so, we come to new forms. We call this constructive thinking, or the atelier way of working. That is really our design ethic, and for us that works really well.

Does design imply the idea of objects that are necessarily useful?

SS: Not necessarily. From the point of view of a designer, we think a product should be functional, but aesthetic and proportion are just as important for design.

CB: Working with the [design] industry is extremely important for us; that is where the greatest problems and also the greatest opportunities lie. Our aim is to arrive at a product in collaboration with industry that will contribute something unique, and in that sense, it should be useful in one way or another.

Is it able to cooperate in the creation of works reserved solely for pleasure?

CB: Designing a product is serious business. It depends on how you interpret pleasure.

Ought form derive from the analysis of function?

CB: We think form follows function. We always start from an assignment to work with a certain craft, or material, or technique, and we become passionate once we recognize the potential of this material or craft.

Can the computer substitute for the designer?

SS: No, never. The starting point for designs, next to the design brief, is a gut feeling of what is going to happen in the future. A computer could never predict this. It could perhaps calculate it, but you still need the intuition to create a design, or come up with the first initial idea to start the design process.

Does design imply industrial manufacture?

CB: By creating limited edition, mass-production products, we learn to collaborate with industry. Our aim is to arrive at the product together and come up with something unique to the world. For us that is very important.

Is design used to modify an old object through new techniques?

SS: There are always some product typologies, such as a chair, which can be renewed because of new materials and new technologies. And sometimes there are completely new product categories like mobile phones. In the future, there will be new product categories which have totally new design principles.

Is design used to fix up an existing model so it is more attractive?

CB: Re-editions are very popular. And with the new techniques and materials and other design practitioners, these products can be produced again. We can only hope our products will be redesigned in the near future by new generations. I think that’s a compliment.

Is design an element of industrial policy?

SS: Not necessarily, because it is sometimes necessary to make a statement within the design process [that] is anti-industrial. It is always industrial related, and that’s how we describe design or show the difference between design and art.

Does the creation of design admit constraint?

CB: Every culture and every method has its own constraints.

What constraints?

SS: Color is always a constraint. The color range of glazing is totally different than the color range of printing or textile weaving.

Does design obey laws?

CB: For us, design is very free. It’s a process of creation, it’s about durability, functionality, aesthetics.

Are there tendencies and schools in design?

CB: They come and go. A couple of years ago, it was about edition design, and now it’s super social. You also see young designers creating materials–not really products, but materials that other people can maybe use for their products or interiors.

Is design ephemeral?

SS: Design is getting more and more important in our daily lives. Not only product design but also the design of processes, or routing, or information. With all these people on Earth, we cannot do without design, because it enables us to have a better life, a better process of life.

Ought design to tend towards ephemeral or towards permanence?

SS: The challenge we have as designers is to solve these issues. You will design garbage that is thrown away or needs to be recycled and that’s the challenge we face, especially industrial designers, where things have to be separated into durable or ephemeral.

How would you define yourself in respect to a decorator? An interior architect? A stylist?

CB: We create the products, and they apply them. That would be ideal.

To whom does design address itself: To the greatest number? To the specialists or the enlightened amateur? To a privileged social class?

CB: We design specifically with the public in mind, and we design from limited edition to mass production. We think everything in between is interesting because it is all different markets with different requests. So, it’s from greatest numbers to a very private social class, depending on how it’s made and the price that comes with the production process.

After having answered all these questions, do you feel you have been able to practice the profession of “design” under satisfactory, or even optimum conditions?

SS: We feel like a doctor who has finished his Master’s degree. I think we are now learning to be specialists.

Have you been forced to accept compromises?

CB: In designing something new, we have to deal with compromises the whole time. Although it doesn’t feel like a compromise because as we look into parts of the process that aren’t feasible, we have a chance to design what is possible. We make sure it still feels like our product in the end.

What do you feel is the primary condition for the practice of design and for its propagation?

SS: First of all, the assignments—otherwise there is no job. To allow yourself time to study topics. Being interested in new technologies or materials and production processes. To work with the new or younger generation.

CB: Clients that appreciate the finer details and are willing to invest in the processes that take more time, money, and energy but yield better results.

What is the future of design?

CB: Designing the future of the past. Designing a better life, for everyone. We’ll see.